Different Drummers: Eliminating the Hogan Confusion

By Michael Fitzgerald

Introduction

In a number of resources confusion has been sown regarding two entirely different jazz drummers sharing the surname of Hogan. Over the years the situation has worsened rather than improved. What was once accurate has been made incorrect.

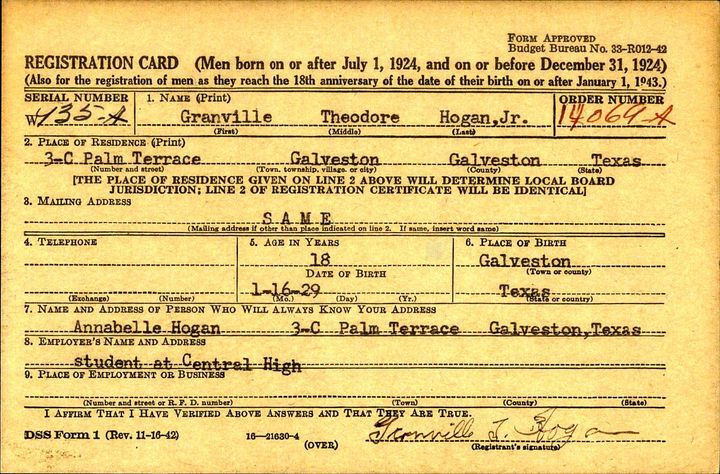

The Jazz Discography currently gives the name as “Wilbert Granville T. Hogan” (69 sessions) while also including “G. T. Hogan” (2 sessions) and “Wilbert Hogan” (1 session). The earlier print edition had separated the musicians correctly. [1]

Figure 1. The Jazz Discography Online, accessed December 29, 2025. [2]

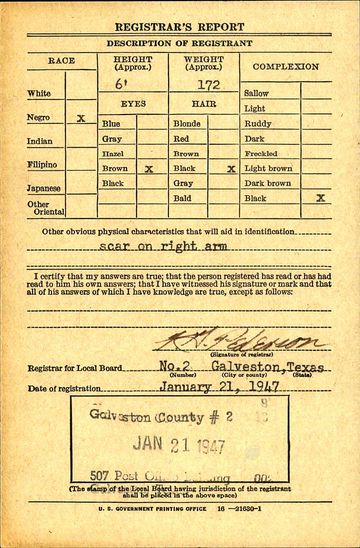

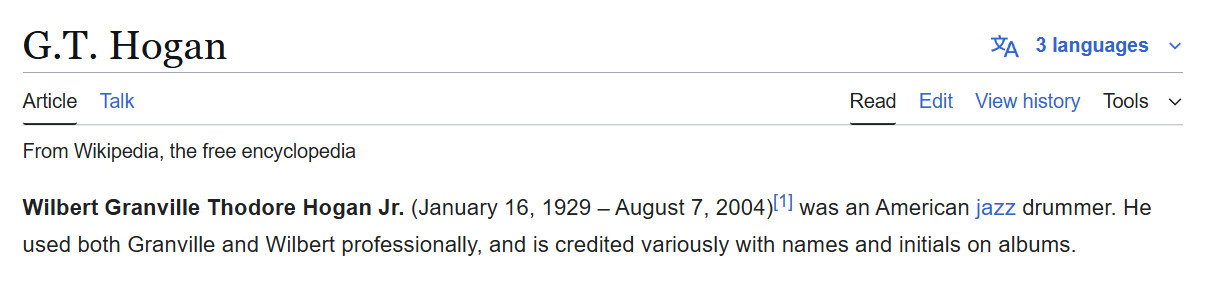

The ever-popular user-edited Wikipedia goes with “G. T. Hogan” and (without any citation) pronounces, “He used both Granville and Wilbert professionally, and is credited variously with names and initials on albums.”

Figure 2. Wikipedia, accessed December 29, 2025. [3]

Many others have subsequently revised discographical entries on web pages, in print, and on reissues, spreading the errors far and wide. [4]

Let it be known now and ever after: these are two distinct individuals. Evidence that they were in any way related has not been discovered. They do have similarities, however. Both were southern blacks born in 1929; both were jazz drummers, active in the 1950s and early 1960s. One particular point of potential confusion is that at different times, pianist Randy Weston recorded with both of these drummers (though in sequence, first Wilbert, then G. T.). Contrary to any source that asserts it, there is no such drummer named “Wilbert Granville T. Hogan.” Certainly there have been musicians who have encountered both drummers and known them to be distinct. [5]

Contemporary credits are generally accurate. It is only in retrospect that some have decided to conflate these two players. This decision is certainly inadvertent and likely stems from good intentions, but among some there is a forceful push to implement the change without any solid evidence or informed reflection. [6]

In this age of digitized archives doing the necessary legwork to establish the truth is not especially difficult, but the results of such research seem never to have been presented previously. In an attempt to resolve this once and for all, here is plain and conclusive evidence as to the individuality of each man.

G. T. Hogan

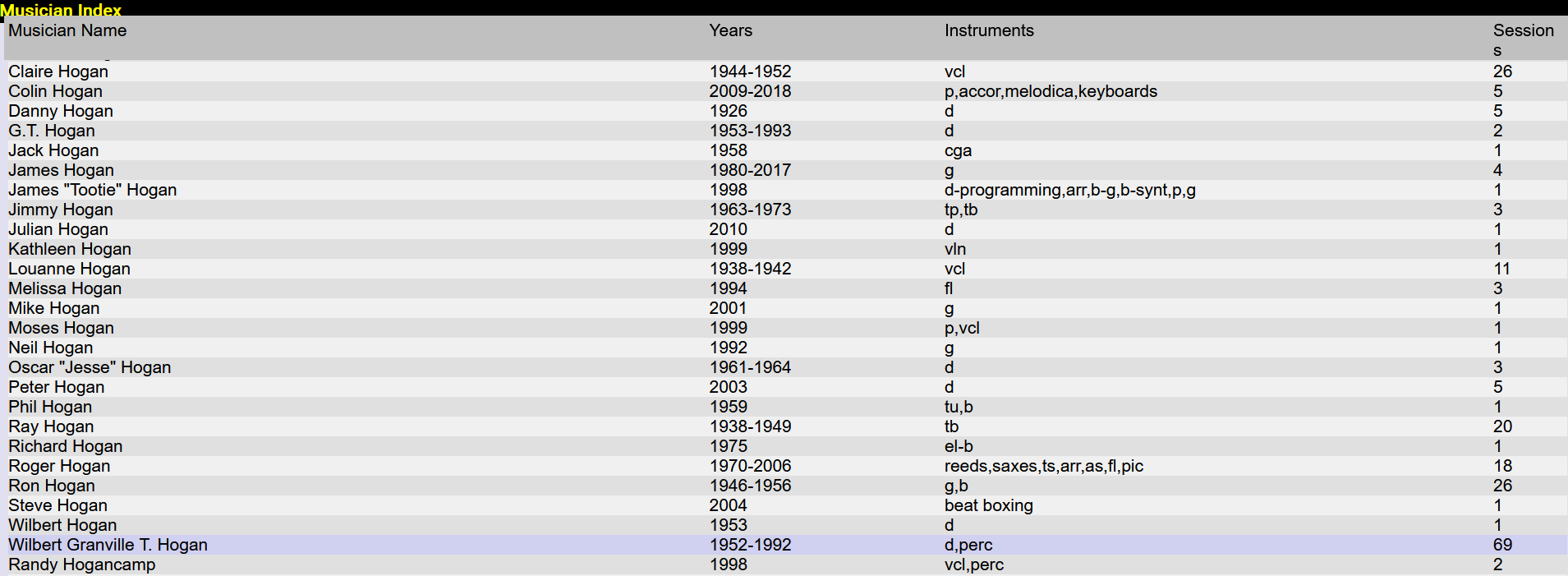

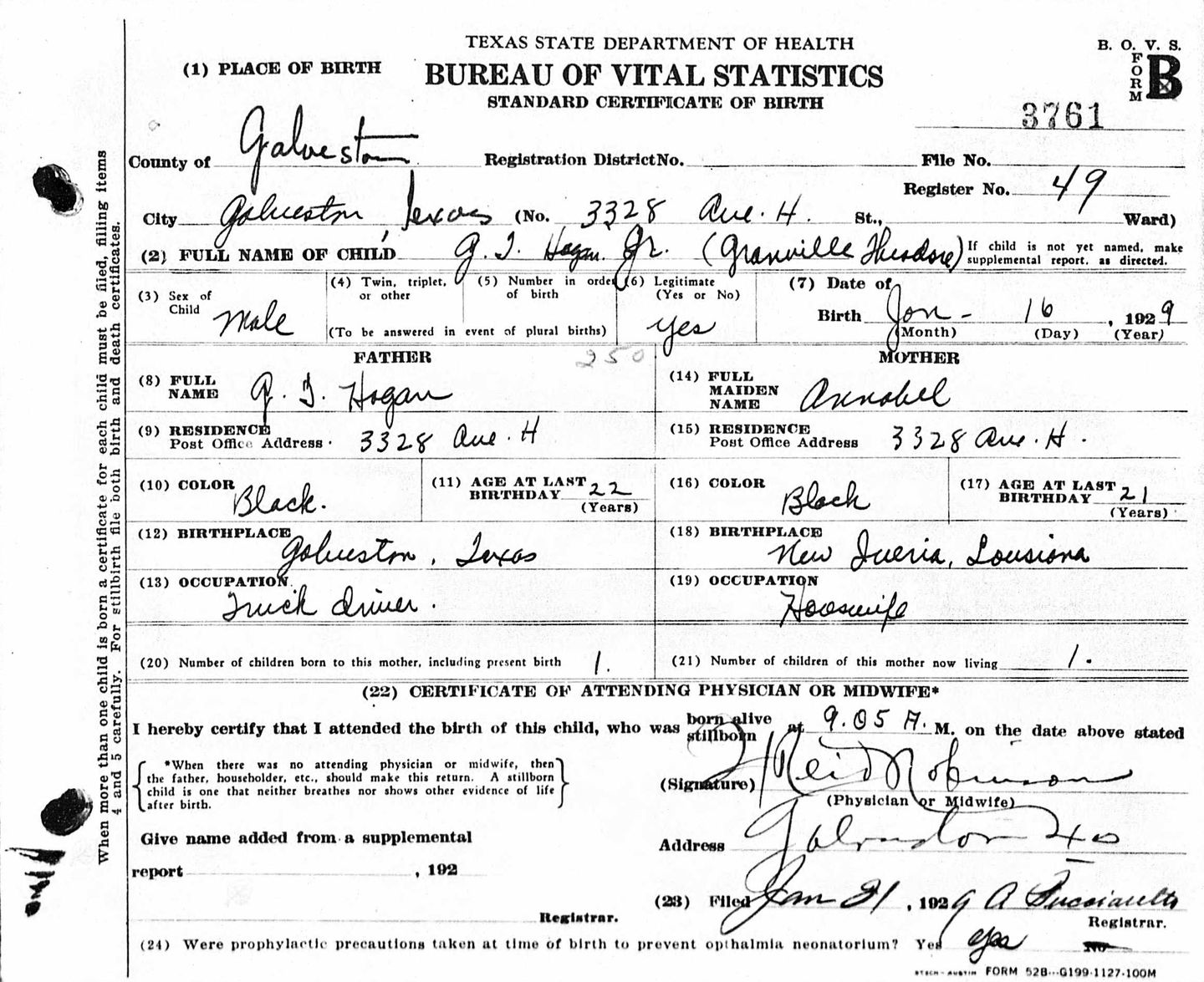

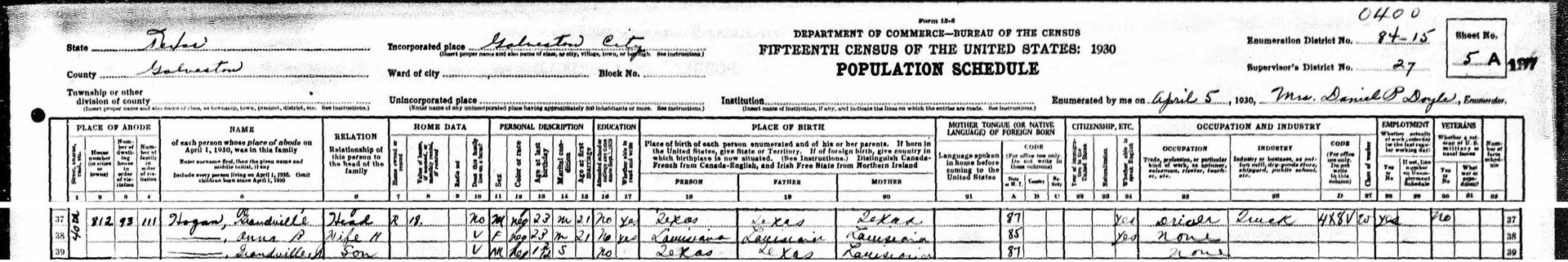

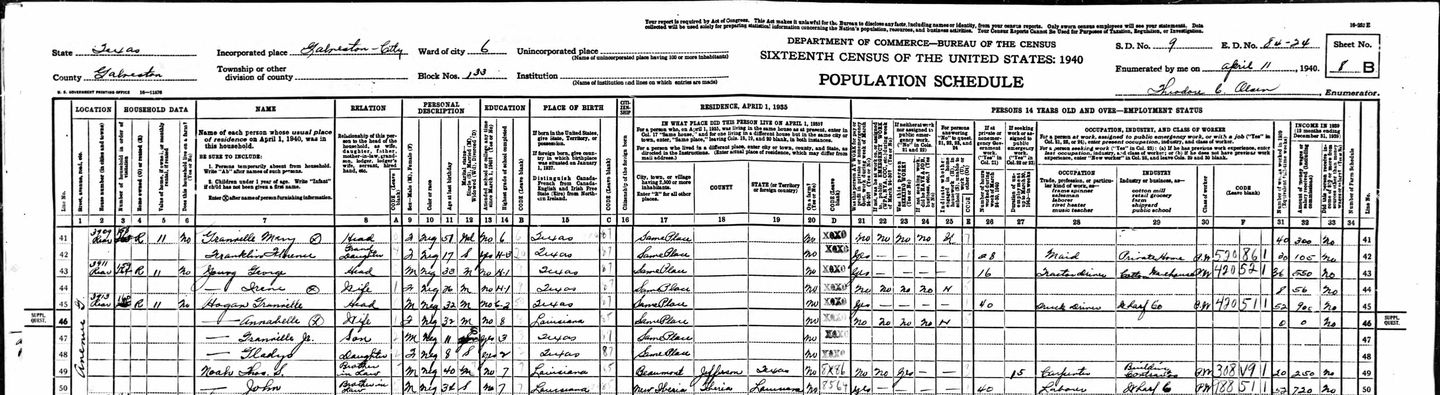

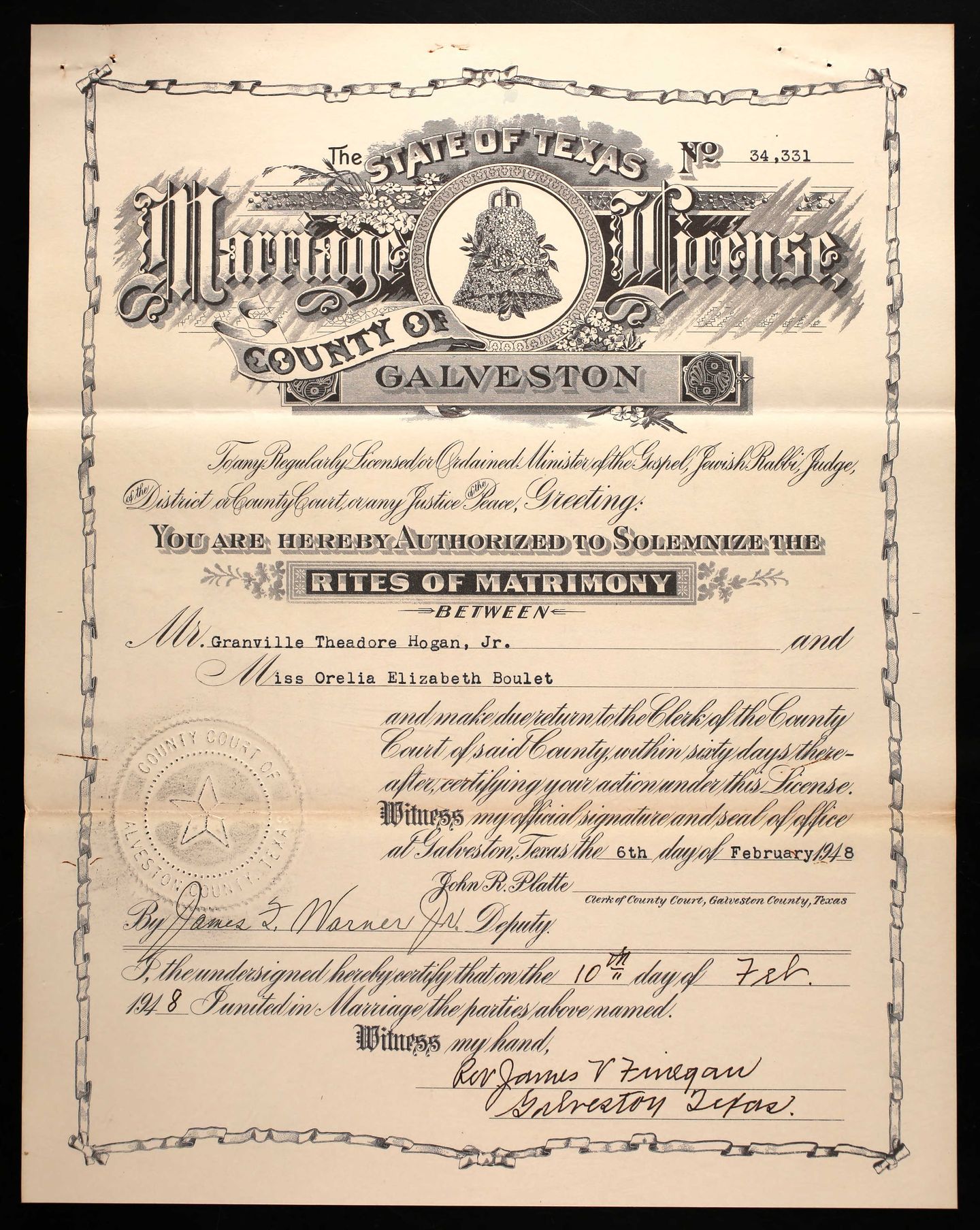

Granville Theadore Hogan, Jr. (known professionally as “G. T.”) can easily be remembered as coming from Galveston, Texas. [7] The unusual spelling of his middle name is as it appears on his typed marriage certificate, although the common spelling is also found in documents. He was born on January 16, 1929, the eldest child of Granville and Annabel B. Hogan. In 1947 he was graduated from Central High School in Galveston, [8] where he played tenor saxophone. [9]

Figure 3. G. T. Hogan 1929 birth certificate. [10]

Figure 4. Family of G. T. Hogan in 1930 U.S. census (excerpt). [11]

Figure 5. Family of G. T. Hogan in 1940 U.S. census (excerpt). [12]

Figure 8. G. T. Hogan 1948 marriage license. [14]

By 1950, he was separated from his wife and working as a musician. He and his two young sons were living with his parents. Hogan’s third child, a daughter, would be born in July of that year.

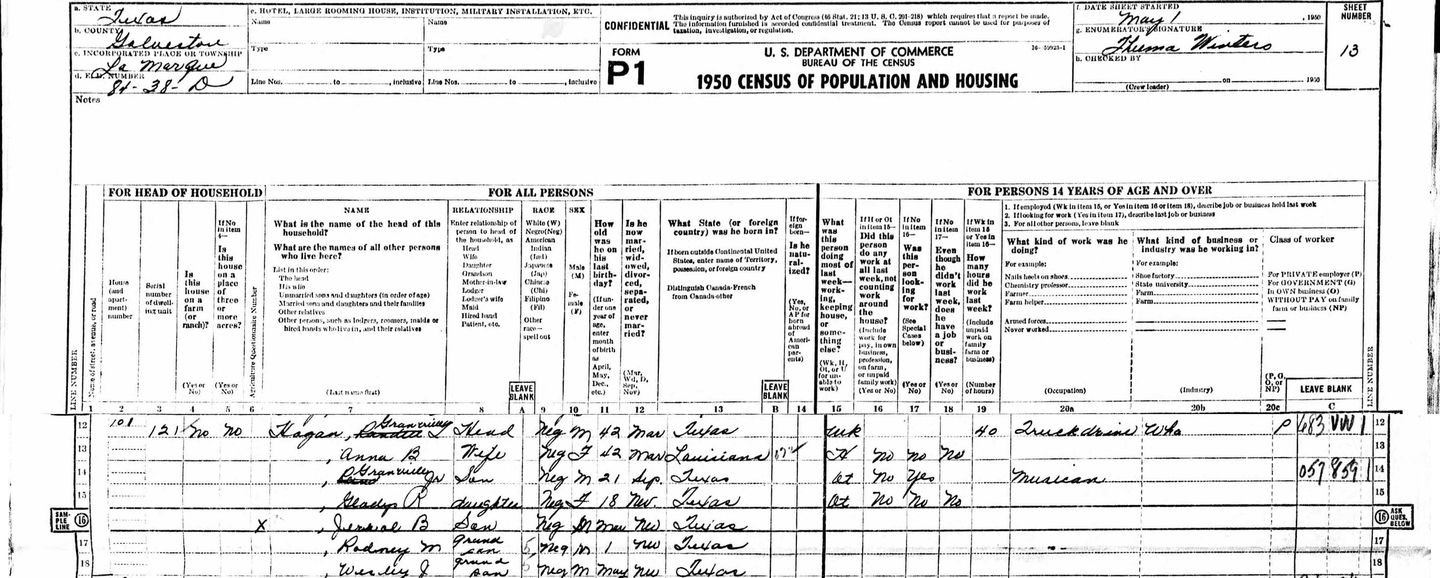

Figure 9. Family of G. T. Hogan in 1950 U.S. census. [15]

As a drummer, his earliest professional job was a long stint (1953–56) with alto saxophonist Earl Bostic, in a very active touring and recording group that included several later notables such as trumpeters Blue Mitchell and Johnny Coles and tenor saxophonists Stanley Turrentine and Benny Golson. Following his tenure with Bostic he recorded with singers Linda Hopkins and Joe Medlin (King, 1956). Hogan then settled in New York and was based there from 1957 to 1962.

Hogan worked with Illinois Jacquet [16] and Stan Getz (1957) [17] before making “what he considers his jazz debut” [18] on Kenny Drew’s This Is New (Riverside, 1957). Two Kenny Dorham LPs followed (Riverside, 1957–58). He was a member of Randy Weston’s working trio, which was recorded in performance at the Newport Jazz Festival by MetroJazz on July 5, 1958, and which played the Village Vanguard later that same month. [19] That year he participated in two albums interpreting the Broadway show tunes of Rodgers and Hammerstein: Wilbur Harden’s The King and I (Savoy, 1958) and Cy Coleman’s Flower Drum Song (Westminster, 1958?). [20]

In 1959, Hogan traveled to Paris, where he played with Lucky Thompson and Oscar Pettiford [21] as well as with Bud Powell and Barney Wilen. [22] Hogan can be seen in short silent film footage of Powell playing at Le Chat Qui Pêche with bassist Chuck Israels. [23] He returned to New York at the start of 1960. [24] His only recording activity that year was with Lee Konitz (Wave, 1960) and Randy Weston (Roulette, 1960).

Figure 10. G. T. Hogan and Chuck Israels at

Le Chat Qui Pêche, Paris, 1959. [25]

The following year he recorded with Cal Massey on Massey’s sole date as a leader (Candid, 1961) and performed as a member of the short-lived International Jazz Quartet alongside Belgian saxophonist Bobby Jaspar, Hungarian guitarist Attila Zoller, and Javanese bassist Eddie de Haas. [26] As a member of Houston-born singer Johnny Nash’s backing group, Hogan traveled to Trinidad that June. [27] He also recorded twice with Walter Bishop, Jr. (Jazztime, 1961; Operators, 1962); Elmo Hope (Beacon, 1961); Curtis Fuller (Impulse, 1961); and Joe Williams (RCA Victor, 1962). Hogan appears very briefly as an uncredited musician in the 1961 film Splendor in the Grass, recruited for the job by the film score’s composer, David Amram. [28]

Documentation of activity after 1962 is rare. After a gap of several years, he appears back in Texas in 1966–67, backing Kenny Dorham, Howard McGhee, and Sonny Stitt at the first Longhorn Jazz Festival in Austin and appearing with local Dallas players at the following year’s festival. In the late 1960s and early 1970s Hogan was based in Los Angeles, where he worked with Jimmy Smith (1968) [29] and Dolo Coker and Harry ‘Sweets’ Edison (1969). [30]

In 1977 Hogan returned to his hometown of Galveston, Texas where he led his own groups and backed visiting artists through the 1980s and into the 1990s. [31] After making recordings with Sebastian Whittaker (Justice, 1992) and Jimmy Ford and Stephen Fulton (Champian, 1993), Hogan was incarcerated in Texas due to narcotics convictions. [32] His final recordings were made in New Orleans with tenor saxophonist Marchel Ivery and organist Joey DeFrancesco (Leaning House, 1999) and in Houston with tenor saxophonist Stan Killian (2002).

In his later years G. T. Hogan suffered from emphysema, and he died August 7, 2004 in San Antonio, Texas at the age of seventy-five.

Wilbert Hogan

While G. T. has brief (but accurate) entries in the 1960 Encyclopedia of Jazz and its 1999 successor The Biographical Encyclopedia of Jazz as well as an entry in The New Grove Dictionary of Jazz, Wilbert has none. [33] In light of this, a more detailed biographical and career narrative will follow.

Wilbert Warren Hogan was born July 9, 1929 in New Orleans, Louisiana, the fourth child of Moses and Almontine J. Hogan. He was a drummer in the New Orleans tradition. Hogan studied music with Professor Valmore Victor [34] at the Thomy Lafon School [35] and Booker T. Washington High School in New Orleans, at the same time as fellow drummers Ed Blackwell, Thomas Moore, and Albert ‘June’ Gardner. According to Gardner, these three were close musical friends: “We’d get together and exchange ideas and practice.” [36] Between 1947 and 1950, Hogan served in the U.S. Army as a member of the 2nd Infantry Division Band at Fort Lewis, Washington, rising to the rank of Sergeant.

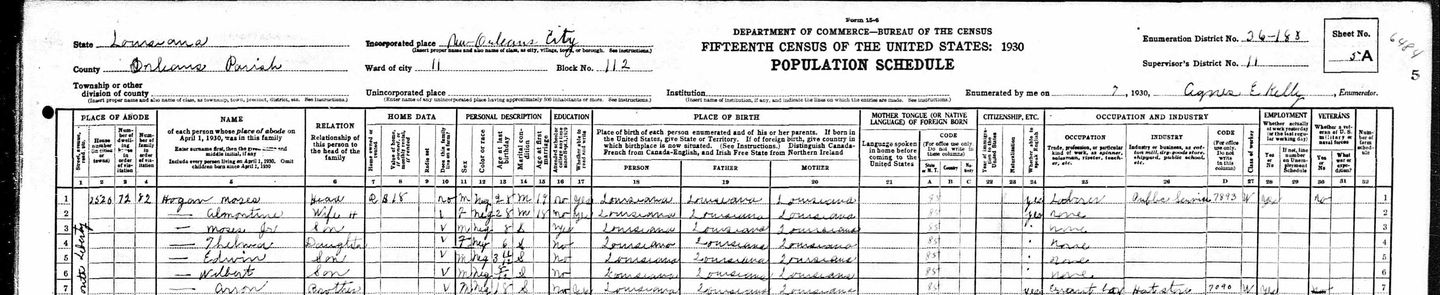

Figure 11. Family of Wilbert Hogan in 1930 U.S. census (excerpt). [37]

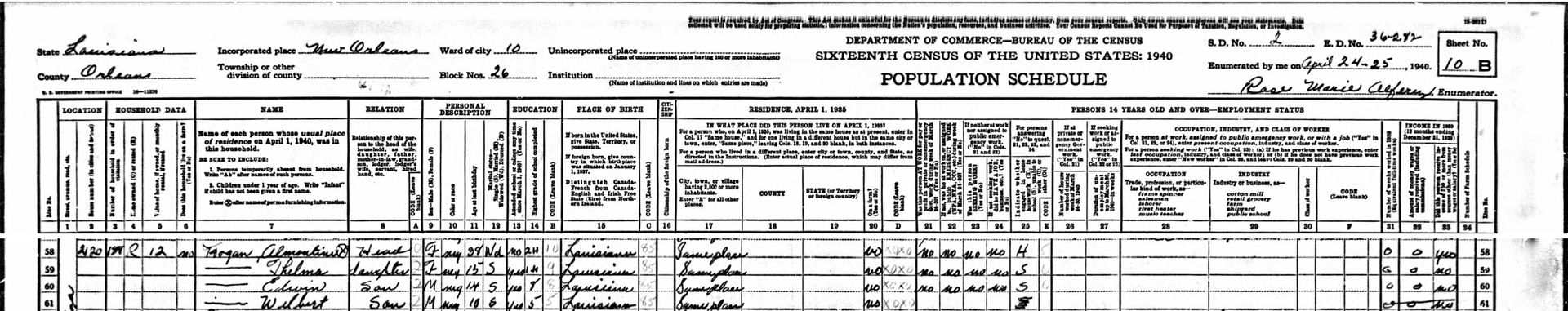

Figure 12. Family of Wilbert Hogan in 1940 U.S. census (excerpt). [38]

His earliest documented work was with Eddie ‘Cleanhead’ Vinson (1952) and Sonny Stitt (1953). [39] It is possible that he attended the Juilliard School of Music in New York in the mid-1950s, although this is unconfirmed. [40] After settling in New York City, he made three recordings with Randy Weston (Riverside, 1955–56; Dawn, 1956 [41]) and one with Earl Coleman (Prestige, 1956). By the beginning of October 1956, Hogan had joined the Lionel Hampton Orchestra. His predecessor in the drum chair was his old New Orleans friend June Gardner, who may have recommended him for the job.

During this segment of his long career as a top bandleader, Hampton continued the practice he had developed earlier in the decade of blending traditional swing with more modern musical elements. The band included young musicians such as pianist Oscar Dennard, trumpeter Richard Williams, and trombonists Julian Priester and Slide Hampton, all of whom leaned to the modern, but Hampton retained traditionalists such as alto saxophonist Bobby Plater, clarinetist Scoville Browne, tenor saxophonist Eddie Chamblee, trombonist Al Hayse, guitarist Billy Mackel, and dancer-drummer Curley Hamner. (Priester recalled, “He had a habit of hiring young people so he didn’t have to pay them like he had to pay older musicians, but for me that was heaven.” [42]) The band’s performances tended to be spectacular, with Chamblee playing long wailing solos, Hampton switching from vibes to drums for percussion battles, and concluding with marches through the audience. Many in the audience were worked into frenzies by these bombastic displays, [43] but there was also disdain from critics and musicians, who were eager to hear the musical inventiveness that was often obscured by showmanship.

The place was packed, and a lot of British musicians were there, including Johnny Dankworth, a bandleader who was a big deal in the Musicians Union. I don’t know what possessed him to start letting out cat calls from the gallery. He later said that the only reason the Musicians Union relaxed their barriers to letting American musicians into the country was on “cultural” grounds, and that since we weren’t playing jazz, we didn’t deserve to be let in. Anyway, there came a break between numbers, and suddenly, as clear as a bell, comes this shout, “Why don’t you play some jazz?” I was stunned. It was embarrassing. The whole audience had heard it, and everyone was shouting at each other. I couldn’t get that concert back under control after that, which is a shame, because I’d planned to feature Jimmy Deuchar on a number. Anyway, I think that was one of my worst experiences ever at a concert. It’s a big thing when one musician criticizes another in public, and especially right in the middle of a concert. [44]

One thing that was essential from any perspective was swing, and the role of the drummer in the Hampton band was crucial. It was the rhythm section, especially the drummer, who was responsible for maintaining the propulsive rhythmic feel without flagging over the course of the extended musical performances, throughout the concert program, and then often repeating the feat set after set in nightclubs or show after show in concert hall appearances. Since 1952, Hampton’s bassists were playing amplified Fender bass guitars, making their task somewhat easier, but drummers had no such assistance.

Beginning in the fall of 1953, Hampton had been spending more time outside the U.S. He returned to Europe the following year, and in 1956 had spent seven months straight there, including side trips to North Africa and Israel. Publicity was tremendous, with a reported “117 front page stories and 38 magazine covers in 16 countries.” [45] Even before they returned to the states, Hampton’s booking manager, Joe Glaser, had plans underway for them to embark upon a second overseas voyage that same year.

In the past it had been difficult for American jazz promoters to gain access to England, due to musicians union restrictions, but now Hampton was booked for a monthlong tour. Perhaps the unrelenting travel was too much for some bandsmen. There were some replacements made in between these trips, including June Gardner’s vacating the drum chair. The band took no time off in the summer of 1956, making a cross-country tour of the U.S. in August and September, with stops in Chicago, Las Vegas, Los Angeles, Albuquerque, Indianapolis, Cleveland, and finally New York. With the new lineup finalized, the band played a week at New York’s Basin Street as a dress rehearsal before making the trip across the Atlantic. While most of the band traveled by ocean liner, departing on October 13, it seems that Hogan missed the boat. He, saxophonist Leo Moore, and manager Gladys Hampton flew to London on October 18, arriving a day ahead of the others. [46] At the conclusion of the tour, Hogan traveled back to New York aboard the Liberté with his bandmates, docking on December 12. [47]

In the spring of the following year, the Hampton band was again planning to leave America, this time for three weeks in Australia. This was a package tour organized by promoter Lee Gordon also featuring the Stan Kenton Orchestra and singers Guy Mitchell and Cathy Carr. To make ends meet, cost-saving measures were implemented, with bands bringing only a skeleton crew and filling the ranks with local musicians from the Denis Collinson Orchestra. Ten musicians including the full rhythm section were selected to accompany Hampton, but Julian Priester, for one, was not.

Lionel Hampton left me stranded in New York. He had a tour of Australia and also on the same tour was Stan Kenton’s orchestra. So the promoters decided for economic reasons to slice the orchestras in half. Take half of Kenton’s orchestra and half of Hampton’s and have the leaders take turns leading this made-up orchestra. It impacted me because I was one of the youngest members of Hampton’s orchestra. So it was decided I would stay in the states. They wouldn’t send me back to Chicago, where I was residing. I had to pay my hotel, feed myself, and also somehow send some money back home to Chicago. [48]

The remainder of the year seems to have been devoted entirely to Hampton engagements, with no outside record sessions. Hogan’s tenure is documented by two record dates in August with the big band (AudioFidelity) and a brief video segment from a television appearance on the October 23, 1957 episode of the television show The Big Record hosted by Patti Page. [49]

At the start of 1958, the Hampton band again traveled to Europe. They stayed more than two months and performed in Germany, Switzerland, Belgium, Italy, and France. The band arrived back in New York on March 17. [50] Two significant recordings have survived to document this tour: audio from two concerts in Stuttgart on January 5 and 6, and the lengthy video footage of a full concert from Brussels, Belgium on February 17, 1958. [51]

Figure 13. Wilbert Hogan performing in Brussels, Belgium with the Lionel Hampton Orchestra on February 17, 1958. [52]

Hampton participated in The Timex All-Star Jazz Show of April 30, 1958, but Hogan is barely visible during the Hampton band portions of the telecast. [53] He can, however, be seen in a series of photographs by Maynard Frank Wolfe from the rehearsals and filming that are held in the collection of the Louis Armstrong House and Museum. [54] Hogan continued his association with Hampton on and off until 1963, appearing on several recordings. During this period Hampton appeared on other television shows, including The Ed Sullivan Show multiple times. It is possible Hogan may appear in surviving footage. Along with Hampton, guitarist Calvin Newborn, and bassist Lawrence ‘Skinny’ Burgan, Hogan participated in recording the soundtrack for the 1960 Saul Swimmer film Force of Impulse. No drummer is visible during the one scene in which Hampton is shown performing. [55]

Other recordings of this vintage that include Hogan were made under the leadership of A. K. Salim (Savoy, 1958); Leo Parker (Blue Note, 1961); and Jesse Powell (Tru-Sound, 1961). Hogan, along with several other members of the Hampton band, accompanied singer Lloyd Price in five 1961 sessions that were issued on ABC-Paramount releases. In 1962 he participated in two Blue Note sessions led by his Hampton bandmate Fred Jackson. One was promptly issued as the LP Hootin’ and Tootin’, but the other waited decades to see its first release in the CD era. The same musicians backed Ike Quebec on Blue Note sessions around the same time.

As mentioned by June Gardner, there is a camaraderie among New Orleans drummers, and around 1963, it was Hogan who encouraged Lionel Hampton to give James Black, who was new to New York, a chance. [56] Black passed the audition and spent a year and a half with Hampton as Hogan’s successor. “Wilbert Hogan was sort of like my passport, otherwise I probably wouldn’t have gotten into anything. He was in with all the local cats and they all knew and respected him. By me being from New Orleans we had a mutual admiration thing going — he’d just pull me on in.” [57]

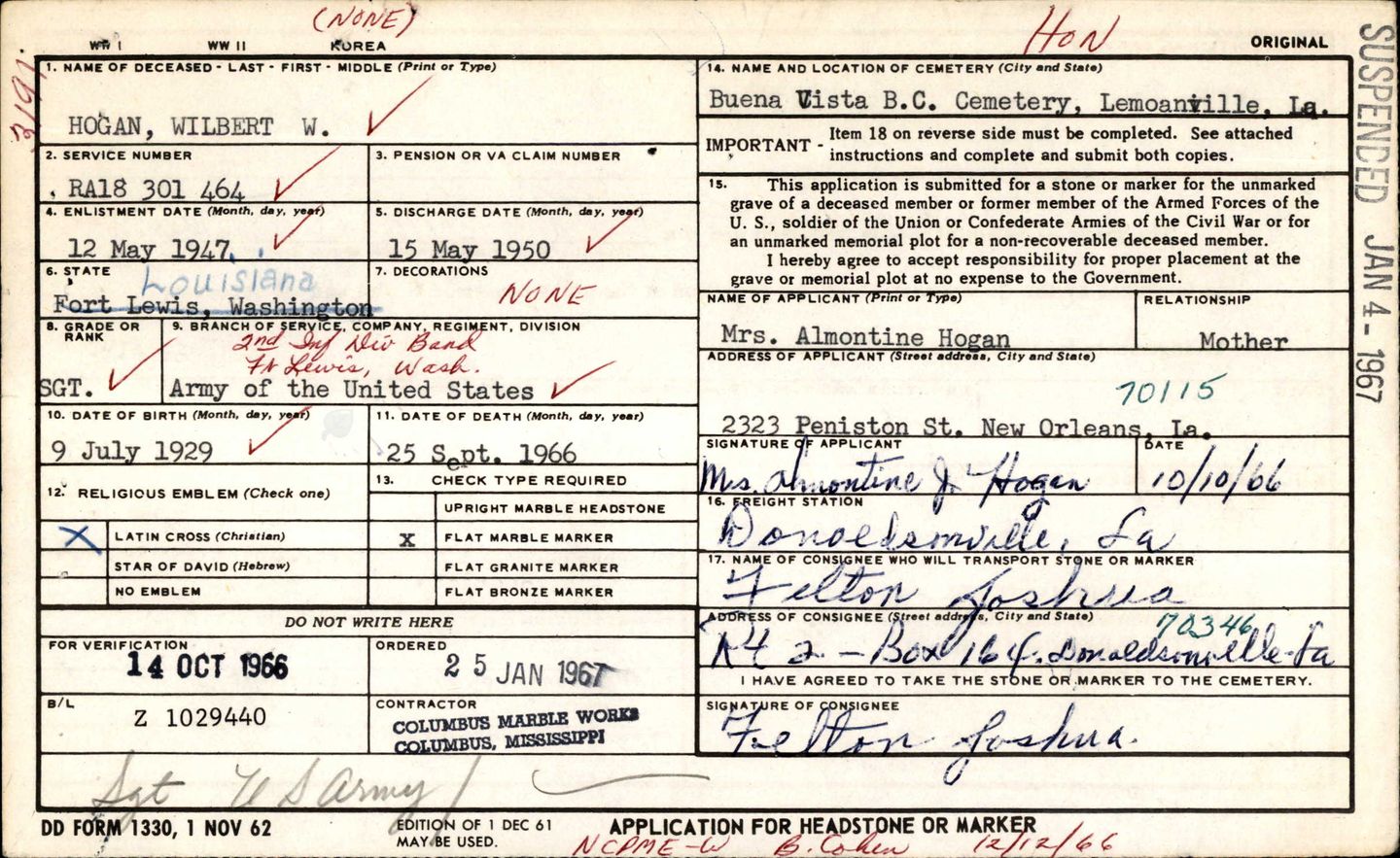

Hogan then became a member of the Ray Charles big band (1963–64), making tours of Europe and Brazil and several recordings (ABC-Paramount, 1963–64). Film of two 1963 concerts from Brazil has been preserved. [58] He also participated in Charles bandmate Hank Crawford’s 1965 and 1966 Atlantic sessions, which resulted in the albums Mr. Blues, After Hours, and Double Cross. After leaving Charles, Hogan joined baritone saxophonist Jay Cameron’s World Beaters group, performing at Birdland and at college engagements. [59] Following this he rejoined Lionel Hampton and was also a member of Frank Foster’s first rehearsal band (1964–66). [60] He died on September 25, 1966 at the age of thirty-seven.

Figure 14. Wilbert Hogan 1966 application for U.S. military headstone. [61]

Conclusion

There is certainly more research that could be conducted with respect to the biographies and professional careers of both drummers. The details of G. T. Hogan’s post-New York years, especially his last years in Texas, are perhaps known only to local players who worked with him and to those who saw him perform. The day-to-day schedules of the Lionel Hampton and Ray Charles bands would give a fuller picture of Wilbert Hogan’s travels during his tenures with those organizations. Nevertheless, the evidence presented here should be more than enough to lay to rest any lingering doubts regarding the unique individual identities of these two musicians. As shown, the confusion is widespread, and it is hoped that this proof can be broadly publicized in order that corrections may be made.

Bibliography

- ‘Almost Slim’ [Jeff Hannusch]. “Gentleman June Gardner.” Wavelength 5, no. 57: 21–23.

- Feather, Leonard. “Hogan, Granville T. (G. T.)” in The New Edition of the Encyclopedia of Jazz. New York: Horizon Press, 1960, 257.

- Hampton, Lionel and James Haskins. Hamp: An Autobiography. New York: Warner Books, 1989.

- Keimig, Jas. “Julian Priester” at Black Arts Legacies, June 19, 2023. https://blackartslegacies.cascadepbs.org/articles/julian-priester, accessed December 29, 2025.

- Kennedy, Al. Chord Changes on the Chalkboard. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press, 2002.

- Long, Barbara. “New Leader in Town: A Portrait of Jay Cameron and His World Beaters,” Down Beat 31, no. 14 (June 18, 1964): 18–19.

- Newborn, Calvin. As Quiet as It’s Kept!. Memphis: The Phineas Newborn, Jr. Family Foundation, 1996.

- Paudras, Francis. Dance of the Infidels: A Portrait of Bud Powell. New York: Da Capo Press, 1998.

- Rusch, Bob. “The Questionnaire.” Cadence 18, no. 11 (November 1992): 76, 107–8.

- Segal, Dave. “Jazz Legend Julian Priester Reflects on His Fusion Classic Love, Love, Sun Ra, Herbie Hancock, and a Lot More” at The Stranger, January 5, 2015. https://www.thestranger.com/music/2015/01/05/21356118/jazz-legend-julian-priester-reflects-on-his-fusion-classic-love-love-sun-ra-herbie-hancock-and-a-lot-more, accessed December 29, 2025.

- Wilmer, Valerie. As Serious as Your Life. London: Serpent’s Tail, 2018.

- Wilonsky, Robert. “The Lull of the Crowd.” Dallas Observer, March 25, 1999. https://www.dallasobserver.com/music/put-up-a-fight-6401144.

Thanks to Mario Schneeberger.

References

[1] “Randy Weston,” The Jazz Discography (West Vancouver, BC: Lord Music Reference, 2001), W484.

[2] The Jazz Discography Online, Lord Music Reference, accessed December 29, 2025.

[3] “G. T. Hogan,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/G.T._Hogan, accessed December 29, 2025.

[4] This even includes those that ought to know better, such as the official Randy Weston website https://www.randyweston.com/

[5] See https://tedpanken.wordpress.com/2011/12/06/an-interview-with-alvin-fielder-july-2002/.

[6] See https://www.discogs.com/forum/thread/1068277?page=1&message_id=11069931 and

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wikipedia_talk:WikiProject_Jazz/Archives/2020_1#G.T._Hogan_and_Wilbert_G.T._Hogan.

[7] Benny Golson is incorrect in recalling Hogan being from Lubbock, Texas in Benny Golson and Jim Merod, Whisper Not: The Autobiography of Benny Golson (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2016), 80.

[8] See https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/145643546/granville-theodore-hogan.

[9] Leonard Feather, “Hogan, Granville T. (G. T.),” The New Edition of the Encyclopedia of Jazz (New York: Horizon Press, 1960), 257.

[10] Texas Department of State Health Services; Austin, TX; Texas, U.S., Birth Certificates, 1903-1932.

[11] Fifteenth Census of the United States: 1930, Population Schedule. Galveston City, Texas; Page: 5A; Enumeration District: 0015; FHL microfilm: 2342068.

[12] Sixteenth Census of the United States: 1940, Population Schedule. Galveston City, Texas; Roll: m-t0627-04037; Page: 8B; Enumeration District: 84-241940 census.

[13] National Archives at St. Louis; St. Louis, Missouri; WWII Draft Registration Cards For Texas, 10/16/1940–03/31/1947; Record Group: Records of the Selective Service System, 147; Box: 703.

[14] Galveston County Clerks Office; Galveston, Texas; Marriage Records, 1947–1948.

[15] Seventeenth Census of the United States: 1950. La Marque, Texas; Roll: 4664; Page: 13; Enumeration District: 84-38D.

[16] Orrin Keepnews, liner notes to Kenny Drew: This Is New (Riverside 12-236).

[17] Harry Frost, “Two Sides of Stan Getz,” Metronome 74, no. 7 (July 1957): 12–13.

[18] Orrin Keepnews, liner notes to Kenny Drew: This Is New (Riverside 12-236).

[19] “Strictly Ad Lib,” Down Beat 25, no. 16 (August 7, 1958): 8.

[20] Recording date often given as 1960, but this LP was “due out this week,” according to Cashbox December 27, 1958: 20 and was reviewed in Cashbox January 24, 1959: 41. It must have been recorded at the end of 1958. According to Billboard November 8, 1958: 27, the show was to open on Broadway on December 1, 1958.

[21] “Strictly Ad Lib,” Down Beat 27, no. 7 (March 31, 1960): 40.

[22] Francis Paudras, Dance of the Infidels: A Portrait of Bud Powell, (New York: Da Capo Press, 1998), 48. Paudras mistakenly gives the name as “J. T. Hogan.”

[23] See https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=l6IuZE5tNS8.

[24] Hogan arrived in New York via Air France on January 5, 1960. The National Archives at Washington, D.C.; Washington, D.C.; NAI Number: 2848504; Record Group Title: Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1787–2004; Record Group Number: 85; Series Number: A3998; NARA Roll Number: 267

[25] Photo is credited to ‘Chenz,’ a pseudonym of Parisian photographer Jacques Chenard.

[26] “All That Jazz,” Cashbox 22, no. 32 (April 22, 1961): 44.

[27] The National Archives at Washington, D.C.; Washington, D.C.; NAI Number: 2848504; Record Group Title: Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1787–2004; Record Group Number: 85; Series Number: A3998; NARA Roll Number: 505.

[28] Bob Rusch, “The Questionnaire,” Cadence 18, no. 11 (November 1992): 76. See also https://www.jazzwax.com/2007/11/interview-david-amram-part-five.html — After nearly half a century, Amram calls the name of the wrong Hogan. Either he or the interview transcriber misspells Wilbert as Wilbur.

[29] “Strictly Ad Lib,” Down Beat 35, no. 12 (June 13, 1968): 50.

[30] “Strictly Ad Lib,” Down Beat 36, no. 19 (September 18, 1969): 36.

[31] Bob Rusch, “The Questionnaire,” Cadence 18, no. 11 (November 1992): 76, 107–8.

[32] Robert Wilonsky, “The Lull of the Crowd,” Dallas Observer, March 25, 1999. https://www.dallasobserver.com/music/put-up-a-fight-6401144.

[33] Mark Gardner in The New Grove Dictionary of Jazz (2nd ed.) concludes the G. T. Hogan entry with, “Hogan should not be confused with the drummer Wilbur (Wilbert) Hogan ( d New York, 1967), who also worked with Weston, toured with Lionel Hampton in 1956–8, and played with Frank Foster’s big band (1964–c.1966).” Unfortunately, this note itself contains several inaccuracies.

[34] Al Kennedy, Chord Changes on the Chalkboard (Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press, 2002).

[35] See https://rafountain.com/news/calvin-boom-boom-manuel/ and https://www.creolegen.org/2015/04/12/the-thomy-lafon-school/.

[36] ‘Almost Slim,’ “Gentleman June Gardner,” Wavelength 5, no. 57: 22.

[37] Fifteenth Census of the United States: 1930, Population Schedule. New Orleans, Louisiana; Page: 5A; Enumeration District: 0180; FHL microfilm: 2340544. Older brother Moses N. Hogan, Jr. was the father of the noted choral arranger-conductor Moses George Hogan (1957–2003). Note that in New Orleans, birth certificates less than 100 years old may only be obtained by relatives or descendants.

[38] Sixteenth Census of the United States: 1940, Population Schedule. New Orleans, Orleans, Louisiana; Roll: m-t0627-01428; Page: 10B; Enumeration District: 36-282

[39] A. B. Spellman, “Herbie Nichols,” Jazz 3, no. 6 (October 1964): 13. This detail was frustratingly omitted when Spellman compiled his earlier articles into the 1966 book Four Lives in the Bebop Business.

[40] The phrase “Of the Juilliard-educated Hogan, Cameron commented [...]” appears in Barbara Long, “New Leader in Town: A Portrait of Jay Cameron and His World Beaters,” Down Beat 31, no. 14 (June 18, 1964): 18. This avenue of research has not been thoroughly pursued.

[41] The LP liner notes quote Weston as saying, “Hogan is now with Lionel Hampton, but we once worked together. Well, Hampton was in town at the time we did this date, so I just thought I’d like to use him.” The recording date of November 21, 1956 usually given for the Weston quintet session that includes Hogan, however, cannot be correct. Hogan arrived in New York from France on December 12, 1956 on the SS Liberté (The National Archives in Washington, DC; Washington, DC, USA; Passenger and Crew Lists of Vessels Arriving at New York, New York, 1897–1957; Microfilm Serial or NAID: T715; RG Title: Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1787–2004; RG: 85).

[42] Jas Keimig, “Julian Priester,” Black Arts Legacies, June 19, 2023. https://blackartslegacies.cascadepbs.org/articles/julian-priester, accessed December 29, 2025.

[43] Crowds sometimes became so wild that police were called. See “Hamp Arrested for Jazzy Exhibition in Amsterdam,” Pittsburgh Courier April 14, 1956, p.32.

[44] Lionel Hampton and James Haskins, Hamp: An Autobiography (New York, Warner Books, 1989), 118.

[45] “Ends European Tour,” Kansas City Call July 20, 1956: 8.

[46] The National Archives at Washington, D.C.; Washington, D.C.; Series Title: Passenger and Crew Lists of Vessels and Airplanes Departing from New York, New York, 07/01/1948–12/31/1956; NAI Number: 3335533; Record Group Title: Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1787–2004; Record Group Number: 85; Series Number: A4169; NARA Roll Number: 409.

[47] The National Archives in Washington, DC; Washington, DC, USA; Passenger and Crew Lists of Vessels Arriving at New York, New York, 1897–1957; Microfilm Serial or NAID: T715; RG Title: Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1787–2004; RG: 85.

[48] Dave Segal, “Jazz Legend Julian Priester Reflects on His Fusion Classic Love, Love, Sun Ra, Herbie Hancock, and a Lot More,” The Stranger, January 5, 2015. https://www.thestranger.com/music/2015/01/05/21356118/jazz-legend-julian-priester-reflects-on-his-fusion-classic-love-love-sun-ra-herbie-hancock-and-a-lot-more, accessed December 29, 2025.

[49] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=R_rTICMVXQQ.

[50] The National Archives at Washington, D.C.; Washington, D.C.; NAI Number: 2990227; Record Group Title: Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1787–2004; Record Group Number: 85; Series Number: A4115; NARA Roll Number: 431.

[51] Lionel Hampton: Live in ’58, Reelin’ in the Years DVD 2.119012, 2008 and https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PZa92eyZIfY.

[52] Screenshot from Reelin’ in the Years DVD.

[53] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OLeQgCqi-6w.

[54] https://virtualexhibits.louisarmstronghouse.org/timex-shows/.

[55] Calvin Newborn, As Quiet as It’s Kept! (Memphis: The Phineas Newborn, Jr. Family Foundation, 1996): 116.

[56] Valerie Wilmer, As Serious as Your Life (London: Serpent’s Tail, 2018), 188.

[57] Ibid, 188–9.

[58] Ô-Genio — Ray Charles Live in Brazil, Rhino/WEA DVD B000641A7M, 2004.

[59] Barbara Long, “New Leader in Town: A Portrait of Jay Cameron and His World Beaters,” Down Beat 31, no. 14 (June 18, 1964): 18–19.

[60] Christopher Kuhl, “Frank Foster: Interview,” Cadence 8, no. 11 (November 1982): 7.

[61] National Archives at St. Louis; St. Louis, MO, USA; Applications for Headstones, 1/1/1925–6/30/1970; NAID: 596118; Record Group Number: 92; Record Group Title: Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General.

Author Information:

Michael Fitzgerald, founding editor of Current Research in Jazz, is full professor in the Learning Resources Division of the University of the District of Columbia, home of the Felix E. Grant Jazz Archives. He is author, with Noal Cohen, of the book, Rat Race Blues: The Musical Life of Gigi Gryce and is coordinator, with Steve Albin, of the website www.jazzdiscography.com.

Abstract:

Various sources have confused two unrelated jazz drummers: Granville T. Hogan and Wilbert Hogan, both of whom were active in the 1950s and 1960s. Through genealogical and biographical evidence, this article aims to establish firmly the individuality and unique identity of each, giving an overview of their respective careers.

Keywords:

Granville T. Hogan, G. T. Hogan, Wilbert Hogan, drummers, jazz

How to cite this article:

- Chicago: Fitzgerald, Michael. “Different Drummers: Eliminating the Hogan Confusion.” Current Research in Jazz 17 (2025). Accessed [date of access]. https://www.crj-online.org/v17/CRJ-HoganConfusion.php.

- MLA: Fitzgerald, Michael. “Different Drummers: Eliminating the Hogan Confusion.” Current Research in Jazz vol. 17, 2025, https://www.crj-online.org/v17/CRJ-HoganConfusion.php. Accessed [date of access].

- APA: Fitzgerald, M. (2025). Different Drummers: Eliminating the Hogan Confusion. Current Research in Jazz, 17. https://www.crj-online.org/v17/CRJ-HoganConfusion.php

For further information, please contact:

Except where otherwise noted, content on this site is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License

This page last updated December 31, 2025, 22:57