Svend Asmussen in Love — Celebrating 100 Years

Anthony Barnett

Introduction

This informal appreciation was originally written for publication (in Danish translation) in the magazine Jazz Special.

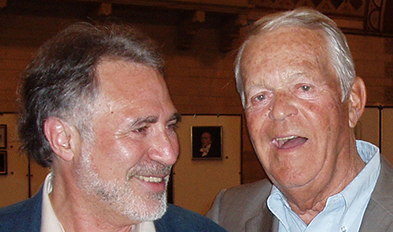

The author and Svend Asmussen in Copenhagen, July 7, 2005.

(Photo by Anna Benedicte Stigen, AB Fable Archive.)

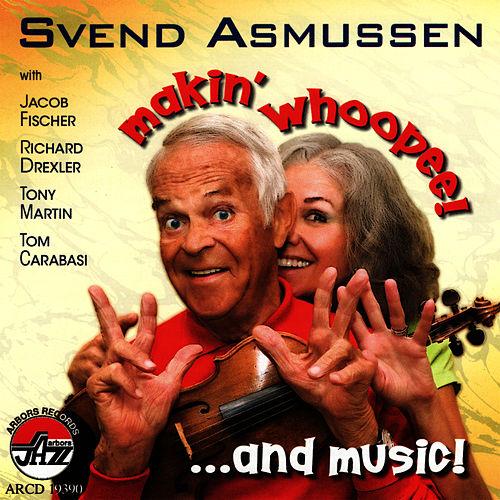

As I write I am listening to Svend’s 2009 Arbors CD Makin’ Whoopee!...and Music! Is that a 93-year old, with wide-open eyes and joyous smile, bursting out of the cover, as his wife Ellen, equally smiling, peeks over his shoulder? It is hard to believe, because that is a perenially youthful face, with the expression of a child who has just entered a marvellous world, and I hear the same exact intonation, fluent technique, and agile phrasing, not to mention impishness, as I hear on his recordings in the 1930s through to the 1990s. At walking speed, perhaps, but that’s all right. And anyway Makin’ Whoopee! is not so many years after Svend was still truly “Running Wild” on a 1996 dacapo/Storyville CD Fit As a Fiddle.

Makin’ Whoopee!...and Music! (Arbors ARCD 19390)

Svend’s playing has a curious effect on my ears. I keep thinking, who does this sound like, where have I heard a violinist like this before? I rack my brains and suddenly I realize. This sounds like Svend Asmussen. Yes, unmistakably Svend Asmussen. It is as if he has a universal style that is nevertheless entirely his own. If one wants to trace antecedents, it is no secret that after early exposure to Danish popular violinist-band leaders Eli Donde and Otto Lington, Joe Venuti is there to be heard on Svend’s 1935 first recordings. But what happens shortly afterwards, after he hears, courtesy Timme Rosenkrantz, those 1936 recordings by Stuff Smith’s Onyx Club Boys? That’s it. That is how the violin is the equal of any other jazz ax. From then on, Svend seeks to harness the violinistic techniques of Venuti with the horn-like fanfare of Smith, serious musicians and puckish humorists both, to create his own serious and funfair voice. In that respect, Asmussen’s instrumental and vocal sextet recordings in the 1940s are among the most entertaining, perfectly formed excursions into small group swing anywhere. With vibraphone, and often clarinet, they are a supercharged mix of Smith’s Onyx Club Boys and Lionel Hampton’s small groups with violinist Ray Perry. Check out their visual appeal too in the film clip Halleluja! I'm a Bum, complete with “Four-String Joe” antics. [1] One particular favourite of mine from the period is “(Give Me) Five Minutes More”. Svend: we don’t think that’s enough. As my co-written contribution with David Flanagan in Grove summarizes: Asmussen’s style is recognizably individual while revealing its debts to Venuti and Smith. He sacrificed the biting attack of Smith, for which he had once strived, in favour of a musical intricacy at times almost filigreelike, with a tone characterized by a veiled, almost muted, quality. [2]

Asmussen has been a happy influence on many jazz violinists, and I want to bring in here the opinion of my colleague, Finnish jazz violinist and educator Ari Poutiainen, who writes:

Asmussen has always fascinated me as a violinist who simultaneously represents both older and modern jazz styles. For some people he might be just one of the great swing violinists but if you study his output carefully you can hear that he has always applied, for example, some modern elements in his improvised melody construction. I appreciate his ability to adjust and apply his creativity to very different musical settings: I’m personally fond of those recordings—Yesterday and Today and Amazing Strings, for example—where he employs some rock or pop influences like back beat and wah-wah pedal. He is light, precise and deep; an accomplished entertainer, conceptualizer, and artist. This kind of combination is rare. [3]

Poutiainen goes on to say that for most North European bowed jazz string players, among them the Danes Kristian Jørgensen and Bjarke Falgren, Asmussen is and has been a model, although you perhaps do not hear violinists directly reflecting his influence that much. Asmussen’s collaborations with other violinists have produced violin summits that are often among the most sophisticated in the field. When Poutiainen was an exchange student in Malmö, the University asked Asmussen if he would give him a lesson or two. He politely refused, saying that he could not teach. But that is not strictly true. The lessons are there to be heard in his playing.

Svend Asmussen and Stuff Smith backstage at the

Violin Summit in Basel, Switzerland, September

30, 1966. (Photo Comet, courtesy Arild Widerøe.)

Admiration for Asmussen extends beyond Europe, not only among jazz violinists but among Western Swing fiddlers too. Johnny Gimble, interviewed by Stacy Phillips, remembered that in the early 1950s he was given an album by Asmussen. He thought it was the best he had ever heard, but he kept hearing violinist J. R. Chatwell in it. Then he found out that both were fans of Stuff Smith. Gimble also makes the point that Asmussen plays the entire fiddle. For perfectly valid reasons many jazz violinists choose not to. Which leads to another aspect of his playing. To adapt that famous Orson Welles advertisement for an internationally renown Danish tipple, Asmussen is probably the best pizzicato jazz violinist in the world. Listen, for example, to Sathima Bea Benjamin’s Enja CD A Morning in Paris, with Abdullah Ibrahim—Dollar Brand, as he was in 1963—and Ellington and Strayhorn sharing piano duties. Not a bow to be heard, but the most moving and sympathetic pizzicato.

There was a time, many years ago, when Asmussen decided that jazz was finished. Later, he found out he was mistaken, that it was not Asmussen who had abandoned jazz but jazz that had abandoned Asmussen. Jazz found out it was mistaken too. They were in love with each other, and they still are.

Happy 100th birthday, Svend.

References

[1] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SeVUb1sQAB4.

[2] Barnett, Anthony and David Flanagan. “Asmussen, Svend.” Grove Music Online.

[3] Private email correspondence with the author, 2013.

Author Information:

Anthony Barnett is a writer and jazz violin historian. His books include Desert Sands: The Recordings and Performances of Stuff Smith: An Annotated Discography and Biographical Source Book and Black Gypsy: The Recordings of Eddie South: An Annotated Discography and Itinerary and Listening for Henry Crowder. He produces CDs of rare recordings on his AB Fable label. His liner notes include Mosaic’s The Complete Verve Stuff Smith Recordings. He played percussion with John Tchicai from 1969 into the 1970s and occasionally with such as Derek Bailey, Don Cherry, Evan Parker, Leo Smith. In 2015 he released a CD of duets with trumpet player William Embling, The Lion in The Grove, recorded in 1980. His website is http://www.abar.net.

Abstract:

An appreciation of the Danish violinist Svend Asmussen (born February 28, 1916) on the occasion of his centenary.

Keywords:

Svend Asmussen, violin, jazz

How to cite this article:

- Chicago 15th ed.: Barnett, Anthony. “Svend Asmussen in Love — Celebrating 100 Years.” Current Research in Jazz 7, (2015).

- MLA 7th ed.: Barnett, Anthony. “Svend Asmussen in Love — Celebrating 100 Years.” Current Research in Jazz 7 (2015). Web. [date of access]

- APA 6th ed.: Barnett, A. (2015). Svend Asmussen in Love — Celebrating 100 Years. Current Research in Jazz, 7 Retrieved from http://www.crj-online.org/

For further information, please contact: